Autism and special interests

A study on how restricted interests compete with social learning in autism with the goal of improving interventions and supports

By Kathryn UnruhKathryn Unruh, of Vanderbilt University, is a member of the 2015 class of Autism Speaks Weatherstone Predoctoral Fellows. Her fellowship supports her study of visual attention, special interests and motivations in toddlers affected by autism. The goal of this research is to guide the development of personalized early interventions that improve social learning and development. She is pursuing this work at Vanderbilt University under the guidance of developmental psychologist James Bodfish, an expert on severe and treatment-resistant forms of autism.

From the first moment of life, experiences shape brain development. A child’s brain development, in turn, shapes his or her social behaviors. Research shows, for example, that most newborn babies like to look at human faces more than anything else. At the same time, their brains tend to respond strongly to the sound of language. These preferences shape our brain development and behavior. They likewise influence how we learn to understand and communicate with each other.

A large and growing body of research also suggests that, early in life, the interests and brain responses of children with autism tend to differ from these typical patterns.

Developing tailored therapies and supports

To develop more effective therapies and supports for people on the spectrum, we need to understand how these differences first appear and when and how they grow.

One widely accepted line of thought is the social motivation theory of autism. It proposes that – even though the symptoms of autism appear around age 2 – most children who will develop the disorder already have decreased interest in social information as babies and toddlers. By social information, we mean facial expressions, voices and other social cues that prove so attention grabbing to most children.

This lack of social interest and engagement, the theory holds, hampers the development of the brain pathways needed to further strengthen interest in people and their faces and voices. These interests, in turn, are crucial to developing social and communication skills including language.

Understanding restricted interests

In my research, I take the social motivation theory of autism a step further by asking: "If young children with autism aren’t motivated to seek out social experiences, then what are they motivated to do?"

This question brings us to the repetitive behaviors and restricted interests that are a core aspect of autism. Classic examples include a baby watching a spinning ceiling fan instead of focusing on his mother as she leans over the crib to coo at him. Another familiar example is the toddler who lines up his toys instead of playing with them in typical ways. Among verbal children and adults on the spectrum, restricted interests can lead to missing social cues and inappropriately dominating a conversation with a narrow topic of interest.

Along these lines, my research also asks:

- Do children with autism engage in nonsocial behaviors because they have no interest in the social cues and information around them?

- Or is the social information around them simply not as engaging as their nonsocial interests?

By focusing on these questions, my research aims to deepen our understanding of autism in ways that can help us better address the challenges these children face as they learn to interact with people and the world around them.

Engaging or competing interests?

For example, many behavioral interventions for autism use children’s restricted interests to keep them engaged. For instance, if a child has a passion for trains, the behavioral therapist might build her therapy sessions around activities with toy trains and/or videos of trains.

One idea I’m evaluating is that this tactic may actually interfere with the goal of developing the child’s social attention and skills. In other words, it might be like asking a child to complete a challenging homework assignment with his or her favorite television show blaring in the same room.

Insights from brain activity

In previous research in Dr. Bodfish’s lab, our team looked at how the so-called “reward centers” of the brain respond to a monetary reward versus a picture related to a special interest (e.g. trains, electronics) in people who had autism. For comparison, we also looked at the brain responses of people who didn’t have autism.

As you might expect, the brains of the people who did not have autism responded strongly to the monetary reward, but not so much to the pictures of objects. The exact opposite was true of the people who had autism. The reward centers in their brains lit up in response to the pictures of objects of interest – but showed less-than-expected response to monetary rewards.

This certainly suggests restricted interests have a significant effect on brain activity – and may decrease brain responses to other information.

In another study, our team used an infrared camera to track what participants were looking at, and for how long, when shown pictures on a computer screen. Compared to typically developing children, those who had autism spent significantly more time looking and exploring pictures of objects versus pictures of faces.

Together, these findings suggest that the extreme nature of restricted interests in autism can play a large role in the condition’s hallmark difficulties with social skills. My Weatherstone project further explores this challenge in ways that I hope will inform and improve autism therapies – especially early interventions.

From insights to improvements in early intervention

One of my aims is to increase understanding of how much different types of information compete with social cues in someone who has autism – and under what circumstances.

By way of example, imagine you’re hungry and I show you a photo of a cheeseburger next to a picture of a puppy. You can imagine which picture will grab your attention.

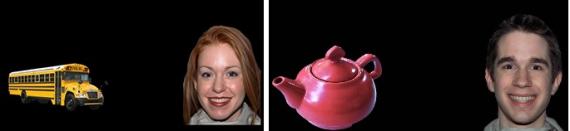

So I pair different pictures together to measure how one image influences a child’s interest in another image. I might pair a picture of a vehicle or a piece of electronic equipment with a picture of a face. (See paired images above left.) Then I might pair a picture of a face with a picture of something that we previously determined is less interesting to the child – say, a teapot or shoe. (See paired images above right.) This enables me to gauge how high-interest versus low-interest objects affect the child’s tendency to focus on social information.

We may find that some children are highly distracted by certain types of nonsocial information and others are not. Time is of the essence when determining which therapy is right for a child, and this may help better understand why some children respond to certain therapies better than others.

The eyes yield further clues

In addition to eye-tracking, I use a method called pupillometry to measure how the pupil of the eye expands or contracts as the child focuses on pictures and their details. Though we commonly think of our pupils responding to dark and light, pupils also expand and contract in response to our interest in the subject of our attention. In particular, I’m studying whether children who have autism show a different pupil response to objects than to faces.

These differences, I hope, can deepen our understanding of how a child is processing social versus nonsocial information.

For example, if eye tracking shows that a child with autism spends more time looking at certain images, I can then look at his or her pupil response. A pattern of extended looking paired with a larger, longer pupillary response may suggest that the child is experiencing pleasure looking at the image and thinking about what it represents.

By contrast, a smaller pupil response may suggest that the longer looking time was more about examining physical details of the image such as color or contrast.

To put it all together, the goal of my research is to show how and why nonsocial information can affect – and potentially interfere – with social attention.

The findings might even lead to earlier intervention. We know, for example, that some of the most obvious differences in social behavior don’t typically emerge until around 2 years old in children who have autism. Distinctive nonsocial interests, however, might emerge earlier and could help us identify children who would benefit from personalized intervention at a younger age.

Including the nonverbal and intellectually disabled

One of the most important aspects of my research, I believe, is that I’m developing testing methods that place minimal demands on children’s language and thinking skills. This means that we can involve nonverbal kids and kids with intellectual disability in our studies. Both of these groups have long been under-represented in autism research and are in great need of more-effective therapies.

In conclusion, I’m pleased to report that my Weatherstone fellowship is supporting the development of new ways to explore some potentially important but understudied aspects of autism. In doing so, we hope it will deepen our understanding of the experiences that shape brain and behavior development and help us design interventions that help these children “get back on track” in ways that foster learning and their ability to function in a socially demanding world.

I want to thank the Stavros Niarchos Foundation, Autism Speaks and its supporters for making this research possible through the Weatherstone Predoctoral Fellowship program.

Learn more about Autism Speaks research projects.