Research yields tips for easing anxiety in nonverbal kids with autism

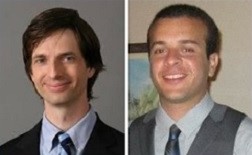

By Dr. Jeffrey Wood and Dr. John DanialThis week’s “Got Questions” response is by psychologist Jeffrey Wood, of the University of California, Los Angeles (above left), and Autism Speaks Weatherstone Fellow John Danial. An Autism Speaks research grant helped support

Dr. Wood’s pioneering work on developing behavioral treatments for school children with autism and anxiety. Under Dr. Wood’s guidance, Dr. Danial’s Weatherstone research project involves adapting these highly effective anxiety therapy techniques for children severely affected by autism complicated by intellectual disability.

I have a nonverbal 6-year-old grandson with severe autism. Going to the lake had been his one great love. He would wade for hours. But on the last of many boat rides, he suddenly reacted badly to the sound of the engine.

Since then, he’s become extremely frightened of any boat engine noise and won’t go near the shore. As soon as he hears even the faintest boat sound (miles away), he dashes to the cottage or car where he feels safe.

What can we do to help?

The following information is not meant to diagnose or treat and should not take the place of personal consultation, as appropriate, with a qualified healthcare professional and/or behavioral therapist.

Thank you for your question. It reflects many that we have heard concerning new fears that have put an end to once-beloved activities such as watching trains or airplanes or even birds. Research has confirmed that anxiety is very common among children – and adults – who have autism.

This is true regardless of where a child may be on the autism spectrum. But no doubt being nonverbal can add to the challenge because the child may feel unable to communicate what’s making him or her anxious.

Naturally, this can likewise be extremely frustrating for family members and other caregivers who want to help the child. We know it’s difficult to see your grandchild struggle with fear and anxiety without being able to effectively communicate with him.

Unfortunately, there have not been many treatment options to help minimally verbal children with autism and severe anxiety.

With the support of John’s Autism Speaks Dennis Weatherstone Fellowship, we are developing and evaluating a treatment program that incorporates strategies designed to help children with communication difficulties cope with anxiety and phobias.

Six children with severe autism and anxiety have now completed the intervention. With further refinement and scientific evaluation, we hope this program will help many children and their families.

Meanwhile, we have been presenting and discussing our program at professional meetings and are glad to share some of its strategies with you today.

7 Strategies for easing anxiety in nonverbal kids with autism

-

Enlist professional help if available

- It’s important to note that the strategies we developed are considered experimental when used with minimally verbal children who have autism. They are adaptations of strategies proven to help children and adults on the less-severe end of the autism spectrum.

- They’ve shown themselves helpful in the hands of trained therapists, and we believe parents, grandparents and other care-givers can likely use them to help children as well. In fact, there are many books on the market about how to help anxious children face their fears.

- That said, we encourage you to involve a behavioral therapist who is familiar with autism as well as your grandson’s pediatrician or other primary care physician. In this way you can reduce the likelihood of inadvertently making the problem worse or otherwise causing undue stress.

-

Approach the anxiety-producing situation in a playful way using beloved characters

- In our program, we use a child’s special interests to talk about the scary situation. Does your grandson have a favorite cartoon, TV or movie character? For example, one might use an Elmo stuffed animal to “act out” the scary situation.

- Let’s use the example of a child who is scared of birds. In this play scenario, you or your grandson might have Elmo happily wade into a pretend lake. One of you could then have a toy bird approach. Elmo might hide his eyes or run away.

- We find it’s important for the child to actively participate in the story. So encourage your grandson to hold and move Elmo and/or the toy bird as you act out the scene. If he’s not ready for that, try asking him to point at the bird or Elmo for starters.

-

Help the child recognize emotions

- As part of this play-based approach, we can gently help a child learn to identify his or her emotions. This process can be as simple as pointing to a picture of a “scared” face when Elmo sees the bird and saying “Elmo feels scared.” As you may know, being nonverbal or minimally verbal doesn’t mean a child doesn’t understand language.

- Recognizing emotions can be an important first step in developing coping strategies. Using a character to model anxiety helps many children calmly think about what’s been frightening them – while making the connection between the situation and feeling scared.

- Editor’s note: Visual supports help many nonverbal and minimally verbal children communicate. Learn more about visual supports and download the Autism Speaks ATN/AIR-P Visual Supports Tool Kit.

-

Develop a soothing phrase, or “mantra”

- We’ve found that repeating a short reassuring phrase, or “mantra,” helps many children with autism face a feared situation. For example, that phrase for the child overcoming a fear of birds might be: “Birds are buddies.” For a fear of airplane noise, it might be: “Airplanes are awesome.”

- Some minimally verbal children can repeat a short phrase they’ve just heard. Some will repeat the same phrase or phrases over and over. For children who have no language, a caregiver can repeat the phrase. In fact, we’ve found that with some children, hearing the phrase is particularly helpful.

- Next, we put these steps together:

- Replay the pretend scenario with the new mantra.

- Once a child has practiced identifying his toy character’s fearful response, you can begin to alter the narrative of the story. Instead of Elmo running away, for example, he may wait in the water and watch the bird fly by. He might listen to the bird’s call and say, “Wow that’s loud!” while staying in the water. Then the caregiver and/or child can repeat that reassuring mantra.

- As mentioned earlier, we found it’s particularly important to encourage the child to participate in the play scenario. So encourage your grandson to hold one of the props or at least point to them as you move them at first.

- Another key, we found, is to make sure the game is playful and positive. In other words, lighten up and have fun!

- In our program, we play-acted the scenario at least several times before beginning what we call the “exposure” phase, which we describe below.

-

Building experience in a slow, safe and gradual way

- This is by far the most important step for easing the symptoms of anxiety symptoms. It is important to remember a key finding from anxiety research: Feared situations must be presented very gradually and with reassurance.

- For a child who is afraid of a type of an animal, for example, we might start by watching an online video of the animal. We might keep the volume muted at first to further reduce any associated stress. At the same time, we’re repeating the reassuring mantra and encouraging the child to do so as well.

- In the fear-of-birds scenario, we might use a variety of videos with different types of birds. This helps promote what we call “generalization.” It’s the ability to apply learning to different situations. In this case, we want the child to experience different types of birds approaching in different ways, with different sounds and in different environments.

- Here again gradual is the key word to remember. We might have a child watch one short, muted video clip per day for the first week. An important part of this phase of therapy is to reward the child with praise and/or a treat each time he or she completes a video clip. This treat might be a favorite activity or snack.

- Future steps can include watching video clips with the volume turned a little higher – again using that reassuring mantra.

-

Stepping out into the real world

- When watching a video clip no longer produces anxiety, the next step might be to watch an actual bird at a distance. In subsequent tries, we might come a bit closer. The grand finale might be a trip to a zoo or sanctuary to see birds up close.

- While we’ve been focused on birds here, the same therapy approach is used for many different feared objects and situations.

- In every case, these steps must be selected carefully based on the child’s needs. Our program emphasizes that every child should feel in control and never too scared.

- It’s equally important that the child show willingness to try each subsequent step in the process.

-

Habituation

- The goal is for the child to become “habituated.” This is a form of learning where someone stops reacting to a situation after repeated exposures. In the case of an anxiety-inducing situation, the fear is reduced considerably, at least under certain supportive circumstances.

We hope these strategies will prove helpful to you and the larger autism community and that they may contribute, ultimately, to a lessening of anxiety problems for people across the autism spectrum.

Need personal guidance?

Contact the Autism Response Team, trained to connect individuals and families with information and resources.