How I learned self-love parenting a child on the spectrum

This blog post is by Lynn Dixon - a mom, writer and advocate for neuro-diverse families. She lives in Seattle, WA with her husband and two sons. You can read more of her work at her blog and follow her on Facebook.

When my son was an infant, before he was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, I accidentally locked him in my car.

After grocery shopping, I strapped him into his car seat. When I went around to the driver’s side, I found it locked. I circled the car in a panic, pulling every handle. All the doors were locked.

I pressed my face against his window. I mouthed through the glass, “It’s okay. I’m here,” but he couldn’t hear me. He started to whimper, then cry, then wail. I desperately scanned the parking lot for something to smash through the window. Finding nothing, I called 911.

Everyone assured me it was a common mishap, the kind of thing that could happen to any frazzled and sleep-deprived new mom. For me, it reflected a deeper disconnect between my son and I.

The first time I recall something amiss, I was getting my son dressed. I had laid him out on the bed, my face dangling above his. I smiled and cooed but, instead of smiling back, he rolled his head away from me.

He became easily agitated. Once he could walk, he’d run around the house crashing into furniture, knocking items from shelves and making small, panicked cries. If I tried to pick him up, he’d push me away or pummel my chest. It felt as though, once again, we were separated by a pane of glass.

I didn’t have children to feel loved, but I certainly thought that was part of the deal, that along with poopy diapers and sleepless nights comes a primal and unsurpassable parent-child bond. As the mom – the one who carried, gave birth to and suckled my son – I fully anticipated being his number one.

Instead, he seemed to prefer even strangers to me. We attended Gymboree classes. At circle time, when other kids sat on their parents’ laps, my son refused to sit on mine. If I tried to hug him to my body, he’d wriggle free and run away.

The less my son wanted to do with me, the harder I worked at getting his attention. On the outside I remained animated and upbeat while inside I desperately wondered what I was doing wrong.

Our relationship had triggered a very old and deep wound in me. I’d always struggled to feel worthy of love and affection. My son’s seeming rejection felt like proof of my unworthiness.

Slowly, I came to realize that I was burdening him with my own insecurities. I’d inadvertently put a vulnerable child in charge of my sense of self-worth. It wasn’t his job to ensure I felt loved; it was mine.

I began to focus more on myself. In those moments I felt rejected, I tuned into my own feelings and tried to self-soothe. When I longed for a look or a hug from my son, I physically wrapped my arms around myself.

At the age of three, my son was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. By then, he was enrolled in preschool and his challenges had become more apparent. He didn’t just struggle to relate to me but to people in general.

Pieces began to fall into place. I learned about sensory processing disorder, a component of autism, where kids on the spectrum become overwhelmed by sensory input. The pattern of withdrawal and aggression I’d observed in my son was his natural fight or flight response to too much stimulation.

In some respects, I’m thankful my son has autism. If he were a typical child who reciprocated love in a more typical way, I would not have had to confront and heal from my own emotional wounds.

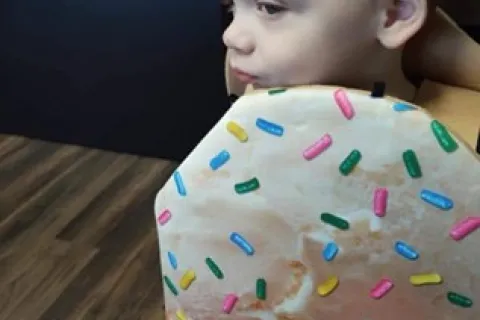

Now I can see how deeply connected he and I actually are. We have our inside jokes and special ways of relating. Now he’s more verbal, he tells me he loves me. Or he’ll grab my face and smoosh it against his own so that nothing separates us.

It still hurts when my son withdraws, or when he is so worked up he’s unreachable. I feel that same stab of rejection. I’m locked out, standing outside the glass, mouthing words he cannot hear.

I take a breath and tell myself, It’s okay. I’m here.